Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Yoshikazu Mano

Industrial designer

Interview: 8 May 2025, 14:00-16:00

Location: Panasonic Design Kyoto

Interviewee: Toyoyuki Uematsu, Shigeo Usui

Interviewer: Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Yoshikazu Mano

Industrial designer

1916 Born in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture

1939 Graduated from Tokyo Higher Polytechnic School of Arts and Crafts, Department of Crafts Design

Joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's Ceramics Laboratory (Kyoto), engaged in export ceramics design

Served in the military

1942 Joined the Design Department, Takashimaya Tokyo Branch, engaged in furniture design (-43)

1945 Joined Koransha, engaged in ceramic design

1950 Professor, Tokyo Higher Polytechnic School. Lecturer, Faculty of Engineering, Chiba University.

1951 Joined Matsushita Electric Industrial. Chief of Product Design Section, Advertising Department, Chief of Design Department, Central Research Institute, and Director of Design Centre

1957 Mainichi Design Industrial Award

1960 Gold Prize at the 12th Milano Triennale

1976 Decorated with Blue Ribbon Medal

1977 Left Matsushita Electric Industrial.

Professor, Department of Craft and Industrial Design, Musashino Art University

2003 Passed Away

Description

Description

“The age of design is upon us.” These are the words reportedly spoken by Konosuke Matsushita, founder of Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. (now Panasonic), revered as a "god of management", upon recognising the importance of design during his visit to the United States in 1951. In response, Matsushita promptly established a Product Design Section within the company’s Public Relations Department. With the introduction from Ryo Takeoka—Head of PR and a university peer of Yoshikazu Mano at Tokyo Higher School of Industrial Arts—Matsushita invited Mano, who was then a lecturer at Chiba University, to serve as design section chief. As Mano had only just joined the faculty at Chiba, it is said Matsushita himself paid a courtesy visit to the university president.

Welcomed with great respect, Mano immediately began work on product designs for radios, televisions, electric fans, and refrigerators. Records show that by 1955, he had filed applications for 183 design registrations. At the same time, he was deeply committed to teaching young designers and later submitted registrations jointly with them. Mano thus became Japan’s first in-house designer and head of design, shaping Matsushita’s design approach through multifaceted practice in product design, talent development, and organisational management.

In 1957, the third Mainichi Design Award (Industrial Design Division) was conferred on “The Matsushita Industrial Design Group led by Mr Yoshikazu Mano and their works,” bringing public recognition to Matsushita’s design innovations under Mano’s leadership. Subsequently, Mano contributed to the broader design landscape in Japan, serving as Chairman of the Japan Industrial Designers' Association and as a professor at Musashino Art University.

Today, the majority of industrial design in Japan is produced by in-house designers. Though many of them exist anonymously under the umbrella of corporations and brands, the scale and quality of their output is remarkable. Yoshikazu Mano, who lived through the formative and developmental phases of Japan’s in-house design movement, consistently explored the ideal relationship between business and design, and laid the foundations that enabled Japanese products to gain international acclaim.

This investigation primarily focuses on freelance designers; however, tracing Mano’s legacy is indispensable to understanding Japan’s industrial design archives.

For this piece, we spoke with Mr Toyoyuki Uematsu, former President of Panasonic Design, and Mr Shigeo Usui, current Executive Officer in charge of Design at Panasonic Holdings. Through the lens of "Mano and Matsushita Design", we explored the inheritance of the Mano philosophy as an archival legacy and examined the design DNA of Matsushita (Panasonic).

Masterpiece

Main works

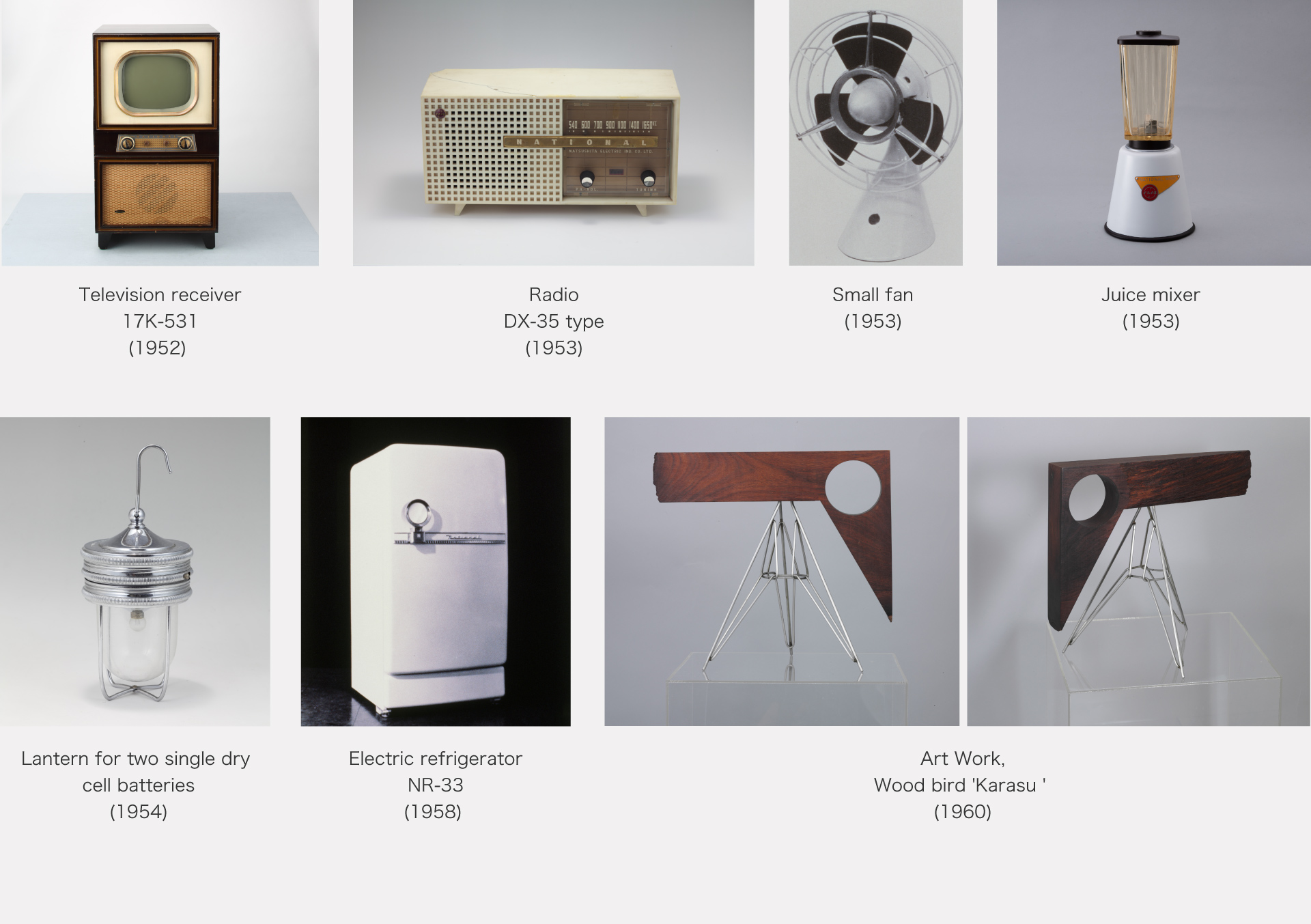

Electric pot C5-421 (1952)

Television receiver 17K-531 (1952)

Radio DX-35 type (1953)

Small fan (1953)

Juice mixer (1953)

Lantern for two single dry cell batteries (1954)

Electric refrigerator NR-33 (1958)

Art Work,Wood bird 'Karasu ' (1960)

Main publications

“The Wooden Bird - Ideas and Moulding “, Nihon Bunkyo Shuppan (1974)

Interview

Interview

Mano-ism: A Commitment to Careful Future Creation

Encounter with Yoshikazu Mano

ー Today, we are talking about Yoshikazu Mano, who was almost the first Japanese electronics manufacturer to establish an in-house design department. First, Mr Uematsu, who was trained by Mr Mano himself, will talk about his first encounter with himself and his character.

Uematsu I am probably one of the few people who knew Mr Mano before his death. I first met him in March 1970, when I spent two weeks on an internship at the Design Centre of Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. At first I was the only one there, so I experienced the design scene and participated in materials research meetings at the Design Centre, where he was the director. After the end of the working day, he invited me to dinner and we talked about design and the profession of a designer in general. After a while, two students from Chiba University joined us, so we were transferred to the Design Department of the then cutting-edge Ibaraki Television Headquarters, where we were taught the process from design to presentation on the assignment ‘The TV you want’.

ー It was a valuable experience for Mr Mano himself to invite you, a student, to dinner.

Uematsu I studied at Musashino Art University and Mr Mano studied at Chiba University under same Professor Katsuhei Toyoguchi, so I felt a connection as we talked. I also got the impression from his conversation that, from his position as director of the Design Centre, he seemed to be in a bit of anguish about ideal design and his own position in the industry.

ー What exactly do you mean by that?

Uematsu Mano's design philosophy was based on the design philosophy of his alma mater, Chiba University, namely ‘Form Follows Function’ and ‘Less is More’, which were the orientation of Bauhaus and Ulm School of Design. ‘Form Follows Function’ was originally a phrase by the American architect Louis Sullivan, and is the basis of modern design. When I met him in 1970, Matsushita had a division system. Mainstay products such as televisions were designed by the design department of each division, and the Design Centre, of which he was the director, did not design any of the mainstay products. In other words, at the time, priority was given to designs that would sell, and I assume that this was not an environment in which his design philosophy could be utilised. However, I now understand that Matsushita's design is overseen by someone with a solid design philosophy like Mr Mano's.

ー Did you join Matsushita directly after your internship?

Uematsu I had an interview and received a job offer. I joined the company the following year, in 1971, and my first post was in the flowery Television Division, which was the same department as the internship.

ー You were a bit distant from him at the Design Centre?

Uematsu Mr Mano was not my direct boss, but we did have contacts. One was the “Bird Modelling Training” that Mano ran, which he continued for some time after he left Matsushita. It was something that every Matsushita designer had to go through.

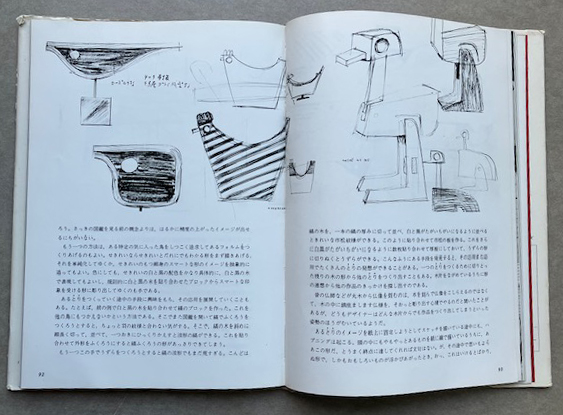

ー The main purpose of the modelling training is described in his book “Wooden Tori(bird)”, isn't it? From there, I think it encourages in-house designers to take a break from their daily routine work and rediscover the pure devotion to modelling.

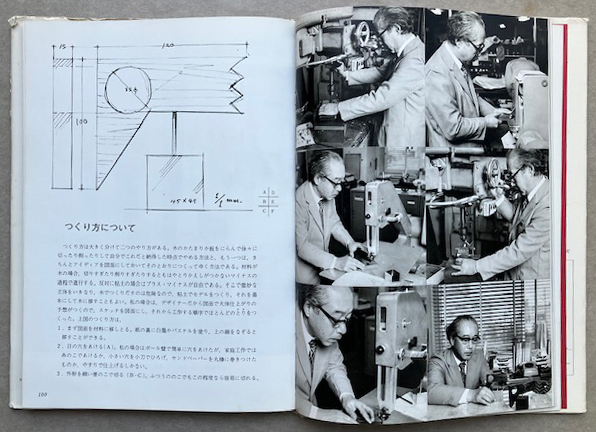

Mano working on his creation with his “Tori sculpture”. (Reprinted from “The Wooden Bird ”)

Uematsu The theme of this modelling training seems to have changed from year to year, but in my case the assignment was ‘National Bird, Honda Bird and Braun Bird’, and we modelled a bird inspired by each of the three companies. I think Mr Mano choose these three companies because the design philosophies of each company were easy to represent, for example, National was stable, Honda was aggressive and Braun was conceptual. I believe that his aim was to include Braun amongst the Japanese brands of Honda and National.

ー What was the aim?

Uematsu The head of design at Braun at the time was Dieter Rams. He was born in 1932, graduated from the Wiesbaden School of Production Technology, worked in an architectural office before joining Braun, where he reigned as Design Director from 1961 to 1995, during which time he also taught at the Ulm School of Design. Under Rams' direction, Braun's design philosophy was ‘Less but Better’, aiming for a minimalist functional beauty that had its roots in Bauhaus and Ulm. Mr Mano appreciated Rams's philosophy. However, as the head of Matsushita's design department, he wanted to convey through this modelling training that ‘it is not enough to simply make things simple, there is a need for Matsushita's aesthetic sense and modelling ability’. His aim was not whether the modelling was good or bad, but to give each designer an opportunity to recognise and reconsider his or her own abilities and thinking.

ー When did this training take place?

Uematsu I think it was irregular. I remember that I participated about three times in my third year with the company, when I became a foreman, or when my position changed within the company.

ー How about you, Usui?

Usui When I joined the company in the early 1990s, Mr Mano had already left the company, but he continued with the ‘Bird Modelling Training’ as a special lecturer. However, the theme at the time was not birds but ordinary products, and he would critique the finished work.

ー Was there anything that left a lasting impression on you?

Usui The Matsushita design system in the 1990s, when I was trained, was division system, and good or bad design was often discussed in the context of product quality and legitimacy. However, he referred to “beauty” head-on. In other words, beauty is above correctness. For those of us who are always seeking sales and efficiency, the true beauty and the search for the truth of "what is design? I felt that his point of view, ‘the search for the truth of what design is’, was very fresh, and I felt that he had hit upon the starting point of design. I think he was a professor at Musashino Art University at the time, but he wore a beret and had a unique dignity in his behaviour and appearance.

Uematsu Mr Mano never wavered in explaining to us the importance of the basics of what beauty in modelling is. He would draw sketches with a brush, but the lines were so beautiful that I immediately recognised him as an excellent designer. In this moulding training he told us that the process of drawing and moulding the lines until he was satisfied was what was important. The material used was mostly rosewood, and it was important how to sculpt the bird using the natural shapes created by splitting and shaving the wood, and I think the process helped us to develop an aesthetic eye and insight.

Design sketch with flowing lines by Mano. (Reprinted from “The Wooden Bird ”)

ー So the results the bird modelling training are still alive in yourself today. You were conveying the exploration of design truths through your training in creating the simple form of the bird from primitive materials such as wood, clay and polyurethane foam.

Mano's position in Matsushita

ー I would like to proceed with the story of how Mr Mano established Matsushita's design department.

Uematsu It is generally accepted that Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of the company, recognised the importance of design in products during a visit to the USA in 1951 and decided to establish Japan's first in-house design department as soon as he returned to Japan, saying that “"It was the age of design”. He scouted Mr Mano, a lecturer at Chiba University, as the head of the Design Section.

ー The background to this is described in a text by Konosuke Matsushita himself in “The Form of Matsushita (published in 1980)”, which was published to commemorate 30 years of Matsushita design.

The basis of product manufacturing is to produce products that will be appreciated by consumers. Producers must devote their souls to this. Design, too, must be studied on the basis of this product-making principle. (Omitted)

After the war, when the company began to rebuild its management, I went on my first trip to the USA for three months from January 1951. At that time, I saw and heard many things, but there was one thing that left a strong impression on me when I visited department stores. There were many different types of the same radio on display, and even though there was not much difference in functionality, the prices were different. I wondered why, and when I asked, I was told that the design was different. This made me realise that design also has a valuable value, and I was very impressed. When I returned to Japan, I told those around me that the future belonged to design and instructed them to strengthen the design department.

The person who helped me at this time was Yoshikazu Mano (former director of the Design Centre, now professor at Musashino Art University), who at the time was a lecturer at Chiba University in the Industrial Documentation Section. (Omitted)

I feel that this is finally the era of true design. I believe that we have entered an age in which products that appeal to consumers, products that make them strongly feel the heart of the product, and products in which this is expressed beautifully through design, are chosen by consumers and appreciated by them. (From “The Form of Matsushita" published in 1980)

ー In 1971, when you joined the company, Mr Mano was Director of the Design Centre under the divisional structure.

Uematsu Yes, in the early 1970s, the Design Centre's main tasks were design commissioned by business divisions without design departments, recruitment and training of personnel and public relations. The TV, housing and other business divisions were proceeding from product planning to design development, sales promotion and publicity, so for him, it was unwilling for him not to be able to design the company's main products.

ー Matsushita had a separate company called International Industrial Design (IID, founded in 1962), so there were several design departments within the company?

Uematsu That is correct. Konosuke believed that by having various design divisions, designers could work hard and create better designs that would please customers.

ー Before the establishment of the divisional system, Mr Mano was steadily working to establish and improve his design department in response to Konosuke Matsushita's expectations. In “The age of design” (Kazutoshi Masunari, published by Aesthetic Publishing, 2022), it is written as follows.

When Mano joined the company, there were only three designers in the Product Design Section, including Mano, and for this reason Mano himself was involved in many design developments as head of the Product Design Section.

The activities and product designs of Matsushita's Design Division, led by Mano, were recognised socially when the company won the third Mainichi Design Award (Industrial Design Division) in 1956. This made the existence of the company's in-house design department widely known throughout the world. (From “The age of design”)

Uematsu Before Manno joined the company, it seems that Konosuke Matsushita himself directly oversaw the design of the main products. Manno was the person chosen by the founder. Given his reputation as a craftsman, it is easy to imagine that he took his duties seriously.

ー That's right. From ‘The age of design,’ it can be confirmed that in the early 1950s, shortly after joining the company, Mr. Mano personally handled the design of major products such as electric kettles, juice mixers, refrigerators, handheld lamps, fans, transportation equipment (buses), batteries, radio receivers, record player pickups, and television receivers, and actively pursued design registrations.

In the early days, Mano drew his own sketches and created models to develop designs. Meanwhile, from 1953, he established an educational forum called the Mano Juku to nurture young designers. (Omitted)

In the next stage, after actively developing designs as a designer himself, Mano seems to have focused on nurturing designers and managing design organisations. (From “The age of design”)

ー As Matsushita grew, his position changed from manager of the Product Design Section of the Advertising Department to head of the Design Department of the Central Research Institute and, in 1973, to head of the Design Centre at the head office. The Design Centre was renamed the Headquarters General Design Centre in 1977. While his position increased in this way, with the establishment of Matsushita's divisional system, the main focus of design development also shifted to the business divisions, creating some distance from the design field.

Uematsu The role of the in-house designer is fluid and Mano's design philosophy has changed. The design philosophy I heard directly from he was Raymond Loewy's “MAYA”, namely “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable”. Lowy, born in 1893, was a pioneer industrial designer in the USA, and in Japan he designed the packaging for Peace cigarettes. His American style of thought was distinct from the Bauhaus design philosophy.

ー What is the background to this thinking, Uematsu?

Uematsu Lowy's MAYA was a good match for Konosuke Matsushita's philosophy. Konosuke's first taste of design was in the USA, and it is quite possible that he learned of Lowy's existence during his tour of the USA. If you aim for ‘Less but Better’, it is difficult to be consistent with Konosuke's thinking at the time, which was to ‘provide as many better products as possible’ and ‘A good design is a product that makes the customer happy’. However, with MAYA, it was acceptable, so I was able to convince myself that it was also good design.

ー Has MAYA been successful?

Uematsu Matsushita products, which combined Mano's enlightenment and Konosuke's pragmatism, were a little more expensive than the competition but sold well because of their high quality. I think this was the achievement of Konosuke and Mr Mano.

ー As well as the ‘Bird Modelling Training’ mentioned earlier, you were also responsible for recruiting and training personnel, weren't you, Mr Mano?

Uematsu After the divisional system was introduced, he himself had fewer opportunities to design, but since all the junior designers had studied under him, they naturally came under the influence of his design philosophy and inherited Mano-ism. However, in the case of Matsushita, Konosuke Matsushita was in many ways too great, and opinions differ as to whether he was able to fully demonstrate his abilities.

From Matsushita Design to Panasonic Design

ー Matsushita Electric Industrial changed its name to Panasonic in 2008 and unified its brand from “National” to “Panasonic”. Mr Usui, you are currently in charge of the design division of the Panasonic Group. What are your thoughts on Mano's legacy?

Usui I joined the company in 1990, some 20 years later than Mr Uematsu, and Mr Mano had already left the company. However, I met him for the first time in my third year at the Bird Modeling Training, and that was the only direct contact I had with Mano. Mr Uematsu was the head of the TV division where I was placed for my internship, so he was my first boss.

ー Is there any awareness of Mano-ism amongst Usui's generation?

Usui Ours was a period of rapid change, from “Matsushita for home appliances” to “Matsushita for electronics” and then to “Panasonic”. The emphasis in design was also shifting to how to visualise the invisible technology of electronics. When I worked with him on his training, I realised that he saw the landscape differently from us, in other words, he saw the essence and beauty of form. If this is called Mano-ism, it lives on in Panasonic Design today.

ー How about from the perspective of design management?

Uematsu Mr Mano was recruited directly as a designer for his formative skills by Konosuke Matsushita, so it is doubtful that he was expected to have management skills as well. If they wanted him to manage as well, they would have needed people and systems that could translate his ideas well and get along well with the human resources and corporate planning departments.

ー Albeit, from 1960 to 1965, Mr Mano published an in-house design journal “NATIONAL DESIGN NEWS”, “NATIONAL DESIGN” and attempted to engage in dialogue with in-house designers by exchanging opinions at roundtable discussions. In addition to training in bird modelling, he also apparently presided over the “Mano Classroom” for new designers.

And the centralisation of the design organisation that he was unable to achieve was finally achieved in 2001 with the establishment of Panasonic Design Company and the appointment of Mr Uematsu as president.

Uematsu The division system of Matsushita design structure changed long after Mr Mano left the company, when President Kunio Nakamura took office in 2000 and implemented a design reform as part of a major overhaul. In other words, management established the Panasonic Design Company to strengthen the Matsushita brand and centralised the design department, which was to carry out cross-sectional product design across business divisions .

Usui The highlight of Nakamura's reform in the design department was the introduction of the president's presentation of “V-products *(main products)” twice a year. This was a meeting where V-products checked by Mr Uematsu in advance were brought to the head office and presented directly by the design staff to President Nakamura and the business managers, who then decided on the spot whether or not to commercialise the product, which filled the workplace with tension. In fact, there were almost no NOs because the presentation was for the V-products that had won the selection process.

*V-products are products that are mandated to make a significant contribution to management by achieving a number one market share position in their main battleground (volume zone) In 2002 (FY03/03), the company introduced a series of these V-products to the market and increased its market share.

ー I heard that even at Sony in the 1980s, during the time of Yasuo Kuroki and Hideo Watanabe, there were meetings where the people in charge would directly present their designs to the then top executives, Masaru Ibuka, Akio Morita, and Norio Oga.

Uematsu I was close to Mr Watanabe, so I heard about that, but I was never aware of Sony. The president's presentation at the important V-product design review meeting was basically given by the person in charge. Today, Panasonic has changed to a holding structure and V-product presentations have disappeared, but Mr Usui is now the executive officer in charge of design, and he is doing his best, conducting presentations by the person in charge as well.

Usui As the executive officer in charge of design at Panasonic Holdings, I am responsible for the overall design of the Panasonic Group. We cover a wide range of design areas, including products, services, solutions, user experience, marketing communication, brand communication, R&D and future vision. We have the idea of "What is Panasonic?

ー The current design philosophy, ‘Future Craft’, means always looking to the future and carefully continuing to create (or ‘carefully continuing to create the future’).

Usui This motto was created by Yutaka Negishi, the head of the Design Strategy Office, who succeeded Mr Uematsu. I took over afterwards and changed the meaning slightly, although the words are the same. It means ‘to understand people's thoughts, to fit in, and sometimes to adapt to the place, and to continue to carefully create the future - that is ‘Panasonic Design’. We believe that the craftsmanship in the phrase ‘continue to create the future with care’ is connected to Mano-ism.

ー The word “craft” suggests the importance of physicality, such as the sense of touch and handwork.

Usui That is certainly true. What has been handed down from Mr Mano to Mr Uematsu and to us is to think with both the head and the hands. Mr Mano's “Bird Modelling Training” is a good example. The motto “Future Craft” is the attitude of a manufacturer representing the Japanese tradition of carefully creating each and every item.

ー I can sense this commitment in the fact that you have established a design base in Kyoto.

Usui If we look 10 years into the future, Tokyo is fine, but if we think 100 years into the future, Kyoto is the place to be. It is said that Konosuke Matsushita thought about business in Osaka, but when conceiving a company or society, he thought about it in Kyoto. His publishing company, PHP Research Institute, was also established in Kyoto. In addition, Kyoto has many universities and research institutions, and the Agency for Cultural Affairs has relocated here, making it a true centre of Japanese tradition and culture, and an area where a high quality of life can be enjoyed. In Kyoto, 100 years is a newcomer. In this vein, it was worthwhile to have Panasonic Design's base in Kyoto, and we were happy to open in 2018, Panasonic's 100th anniversary year.

The present and future of Panasonic Design

ー What are your thoughts on the present and future of Panasonic Design?

Usui Recently, ‘user experience’ and ‘sustainability’ have become major themes in the design world, and these themes have been consistently addressed since the founding of our company. In short, the essence of design remains the same: how to enrich the customer's experience.

Uematsu The fundamentals are the same: to make the customer happy. It is not just about superficial appearance, but also about paying attention to the invisible parts, spending money and continuing to be a company that does these things properly.

Usui Uematsu's words ‘Sell, make money and enhance the image’ remain in my mind, but to realise this, not only products but also branding and communication are important, which became easier to control when the jurisdiction of the design department was expanded.

Uematsu Sell, make money and enhance the image’ is my own translation of Mano's philosophy into general terms. It's obvious, but it's easier to get through to people in the business department if we say “sell, make money and enhance the image” than if we say the right thing about design.

ー The Panasonic Group has gone beyond the realm of electronics, and has also entered the invisible realm of design, such as solutions and systems. If that is the case, how will you reflect Mano-ism, the “beauty of form” of the consumer electronics age?

Usui The tools and skills have of course changed, but the things that our designers value are connected. For example, Uematsu's ‘sell, make money and enhance our image’ and the current ‘Continue to carefully create the future’ were originally said by Mano. The current expression of ‘we will continue to create the future with care’ was originally said by Mr Mano and is not new.

ー What about design thinking and design management?

Usui Design thinking is said to be a new concept, but it is a thinking process that can be applied not only to design but also to management and administration, and we have been doing this for a long time. However, I appreciate the fact that this term has brought people who thought design was irrelevant onto the same ground.

ー In recent years, there has been a trend towards fast appliances, led by distributors such as MUJI and Nitori. What are your thoughts on these trends?

Usui Of course, I am taking a hard look at the current situation. However, we are proud of our differentiation in terms of quality, after-sales service and history. However, we must not just rest on our laurels. We have to communicate well so that our customers understand Panasonic's corporate culture and the superiority of our products. That is why it is important for designers to take the initiative in communication and branding, and we actively use methods such as storytelling on social networking sites. We put the customer first, so it is only natural that our organisation and structure will change in response to customer demands as times change.

ー I think Panasonic's design is sleek and beautiful these days.

Usui Thank you very much. Actually, we have been proposing designs like the ones you see today for some time. However, for a long time, there was a time when it was required to stand out from the crowd in the shops. Recently, we have stopped doing that and have been able to commercialise designs that would have been rejected in the past because they didn't stand out. In other words, we are finally able to utilise the vein of good design that is Mano-ism.

Uematsu That's right. That's why we go back and forth between divisional leadership and design centralisation, like a dichotomy.

Usui In the past, we were told to make colourful vacuum cleaners like foreign products, but when we made our own simple white vacuum cleaners, they sold better. We have repeated such natural things up to the present day.

Panasonic Design and Mano's archive

ー Lastly, I would like to ask you about the current status of Panasonic Design's products and archives, including Mano's designs.

Usui In our company, the design department does not archive directly, but the historical and cultural communication office in the brand and communication department is in charge of managing the historical assets of the Panasonic Group. Some of these are on display at the Panasonic Museum in Kadoma. However, epochal designs and other collections are selected and organised by the Design Department and delivered to the museum. In addition, at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka which opens in 2022, the Industrial Design Archives Research Project (IDAP) of companies based in the Kansai region is progressing, so we are donating materials and lending out our collection through a network.

ー The Panasonic Museum in Kadoma has extensive contents.

The design exhibition section of the Panasonic Museum, with a collection of epoch-making products from previous generations.

Uematsu It is difficult to actually store things, so one way is to make a digital archive. If they can be thrown away, at least the three-view drawings and sketches should be digitised and kept. Before the Nakamura reforms, we used to store TVs in a state where they could be projected, but we had to destroy more than half of them at the time of the reforms. The appliances have to be stored dynamically and cost money for maintenance as well as their location.

ー I would like to see the archive of how Japan's first in-house design department was established and the footsteps of Mano.

Uematsu In that sense, Mano’s ‘Bird Modelling Training’ and others are also important archives. It's been turned into a book called “Wooden Birds”, but I'd like to see bird objects and sketches organised and archived.

ー In the 1960s and 1990s, Japan was an advanced country in home appliance design, so those archives are very important. What are your thoughts on using the archive for design development and design education?

Usui Employees of the Panasonic Group visit museums and History Museum from time to time. I sometimes visit them myself, and employees who are struggling listen to Konosuke's voice messages. In this sense, archives and materials that allow us to return to our origins are very valuable.

ー How do you think the archive should be utilised?

Usui Nowadays, AI and other technologies are advancing rapidly, but from the customer's point of view, the question is whether they are really enriching our customers' lives. For example, AI and other high-tech technologies are evolving day by day, but are the designs of houses, furniture and cars really getting better?

In other words, technology is advancing, but what about design? What about formative beauty, such as lines, volume and texture? Isn't it simply consuming? And. This is a topic that is sure to come up in many situations. It is essential to envision the future, but it is also important to look back to the good things of the past and see the future. In this sense, I reflect that we may have been missing the idea of learning from the archive. Looking back at Mr Mano's footsteps today, I was reminded that in recent years, thinking has become too short-term or shifted too much to cost, productivity and efficiency.

Uematsu Even if times change, the consistency of Panasonic Design can be maintained if there is an indicator of Mano-ism or Zenichi Mano's design philosophy. Mano-san may have agonised over management and organisation, but the role he played in Panasonic Design is still relevant today. Thank you, Mano-san.

ー Any last words?

Usui Even if the company structure changes, we believe that the Mano-ism will be passed on. Today, with the development of technology, it is becoming more and more difficult to interact with people and learn from their way of life and from watching their backs, but the basic principle is the transmission of the Mano-ism from person to person. I too have finally come to understand words that I didn't understand when I was young, now that I am in this position. I now want to weave such words and behaviour. We will continue to connect the baton that was started by him.

Uematsu Panasonic Design has come this far as the first company in Japan to create a design department, thanks to the enterprising spirit of its founder Konosuke Matsushita. Even though society, the times, technology and management may change, I hope that you will continue to do your best based on the principle of ‘timelessness and fashion’.

ー From the customer's point of view, I would like to watch Pass the Baton of Panasonic Design's Mano-ism. Thank you very much for your valuable talk.

Panasonic Design Archive Locations

Panasonic Museum

https://holdings.panasonic/jp/corporate/about/history/panasonic-museum.html